This past week we reunited with Connor, progressed with trainings in the Cyaruzinge community, and napped. A lot.

Daily Breakdown

On Monday we picked Connor up from the airport (aw yeah) and took Hannah and Connor to where they will be living. Their new housemates, Amber and Yannick, are a unique pair. Amber is an American with a Masters in Public Health, a policy and technical advisor for HDI. Yannick is Rwandese but has spent much of his life abroad in South Africa, Burundi, and a brief stint in Canada where he played basketball at university.

After meeting the housemates, we then took Connor to explore a bit more of Kigali and to meet Rachel and Sarah’s housemates, Kaleigh and Julie. K&J adore Connor, naturally. Their first impression of Connor was his deported-to-Dubai blog post… now they ask him how he’s doing on a regular basis out of concern for his assumedly fragile emotional state.

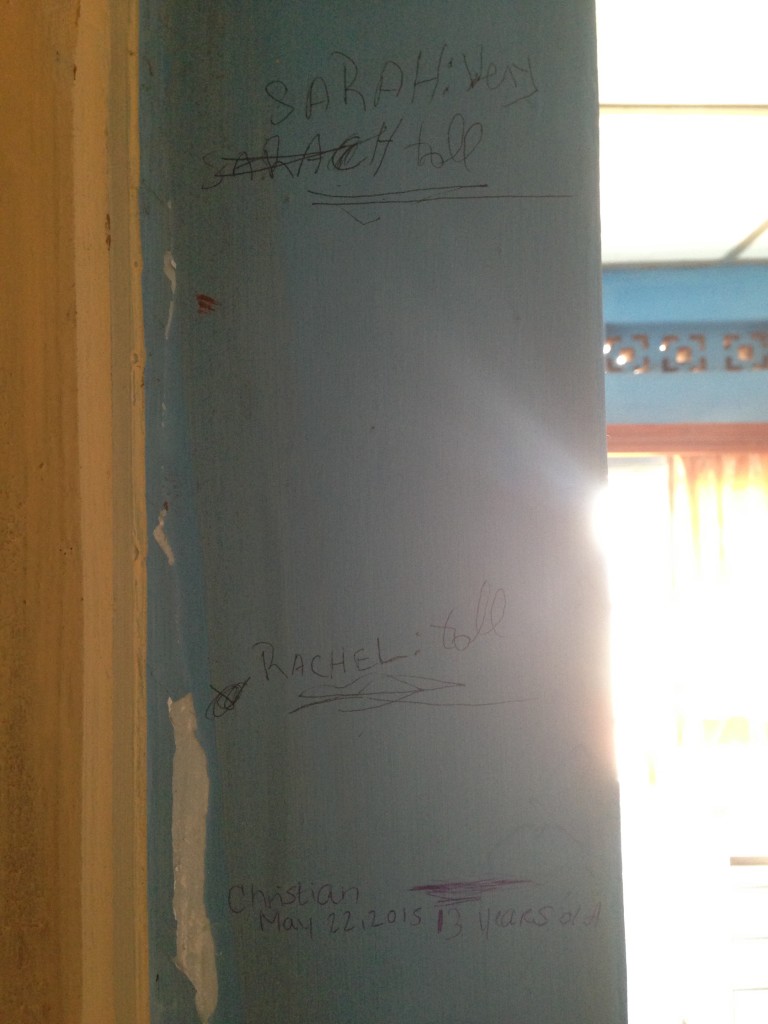

On Monday before we left the house for dinner, we answered the doorbell to a young boy who claimed to know Kaleigh and Julie. After a quick phone call to Kaleigh, we learned that his name is Christian and that he comes over for dinner a few times a week. We had to turn him away that night because we were home alone and hadn’t prepared any food, but he has since come over two or three times for the evening to eat with us, hang out with Theó, and play endless rounds of Angry Birds on Sarah’s iPad. He is an extremely bright boy, constantly working on his English skills. He also loves to play soccer, always mentioning it when we ask about his day. Kaleigh and Julie feel like his mom sometimes, paying for his school fees and supplies as well as haircuts and other general small costs. He first met them one day when he asked for lunch at the gate, and has come to visit the house fairly consistently ever since. While they seem to have made a positive impact on his life, there is some concern about what he will do when they leave Rwanda in the middle of July and are no longer able to support him. This led us into a larger conversation about cultivating relationships over a short period of time and then leaving.

On Tuesday, a miscommunication in the office meant that we weren’t able to help pick out knitting materials; rather, our rockstar facilitator Ronah came at the end of the day with a huge supply of yarn, needles, mats, and one French/Chinese knitting machine. Said knitting machine has proven to be quite an enigma – after struggling with it for a few days, Rachel and Sarah discovered that one tiny yet semi-crucial piece has broken off that could produce a hole in any knitting project. More assessments (and hopefully repairs?) to come.

We discovered that some members of the Cyaruzinge community make brochette sticks using resources they have access to; they’re able to convert some of these into a hearty supply of double-pointed knitting needles using a sample we gave them. This was really encouraging to us, as we hope that this will reduce the need for outside material dependence and will allow the community to utilize some of its own resources to keep the knitting project running.

Tuesday also provided the first opportunity for the business interns to sit down in the office and hash out ideas for the first training. Getting to talk through some preliminary anxieties and logistical questions was cathartic. We later came together at Julie and Kaleigh’s house to make curry (multicultural amirite) and spend time with Cristian and Theó and the rest of the team.

On Wednesday, we had our first training (yay!). It was rescheduled to the afternoon because the women were busy in the morning, and we only ended up training for about an hour because there was a cell (Rwandan equivalent of a neighborhood, but more officially run) meeting. After the training, Sarah was feeling fairly ill, so she went home and slept for most of the afternoon. Connor, Hannah, and Rachel went with Toussaint to Kimironko to pick up the kitenge pants (trousers, to Sarah’s British relatives) the three girls had made by Toussaint’s friend Alexi last week. Pleased with Alexi’s work, the team reunited at home and enjoyed an evening of “fertile” conversation.

On Thursday, we met up with Kalvin, a quirky man we met in the airport who attempted to help with the Connor situation, at the Genocide Memorial Museum. Kalvin is now in the DRC serving as the representative of a California company with a women’s sewing cooperative, working on quality control and troubleshooting.

The Genocide Museum introduces a heavy topic to say the least. It is split into indoor exhibits with outdoor gardens and mass graves. We started with the indoor portion, which was divided into Rwandan genocide, other instances of genocide, and children’s sections. We thought the museum was powerful and sobering and exhibited a hopeful look forward for the country. The inclusion of a half-dozen other historical genocides in the museum really brought home that genocide is not unique to Rwanda. One quotation painted on the wall really stuck out to us. It read something along the lines of “The Nazis didn’t kill 6 million Jews. The Hutus didn’t kill a million Tutsis. They killed one, then another, and then one more, totaling in over a million individuals gone.” It is so easy to lump events like this together and forget that each individual victim had so many loved ones that still feel their loss. The children’s section was also very jarring, showing photos of children who were killed and describing a bit about their favorite foods, best friends, personalities, and how they died. Some were only babies, killed in their mothers’ arms without a second thought. Walking outside, we saw huge concrete slabs on the ground that we found out were the tops of mass graves. Looking at slab after slab, realizing that each was filled with people and that the people there barely made a dent in the total number killed and affected by the genocide was, and still is, hard to comprehend.

Overall, visiting the museum was an enriching experience, as we learned a great deal and thought a lot more about what happened in 1994. The events still touch life here, as Kwibuka banners calling people to remember, unite, and renew are visibly present all over town, commemorating the 21st anniversary. One may wonder if the strict governmental control and resulting safety of Rwanda have roots in the events following the genocide. There is a strong police/military presence on most main roads and government buildings. There are also security guards at most shopping center entrances, put in place even more extensively after the shopping mall bombing in Kenya a few years ago. Walking around town at night feels very safe because of these measures, but it is also strange for us to see men with large guns everywhere we go. One other big difference we have noticed is how united Rwanda seems to us as foreigners. Ethnic divisions are no longer included on identification cards or ever mentioned. Everyone here is simply “Rwandese.” This makes things a bit difficult for the population we are working with, the Batwa people; they are in need of more government aid due to their marginalized status, but the government is moving towards discontinuing their funding on the basis that their community identifies as a separate ethnic group.

Later that day, Kaleigh took us on a tour of Kigali focused on the fashion/textile industry in Rwanda. As an aspiring designer, she has made a lot of friends and business connections that she thought might be helpful for us to meet as we plan what types of products to make and where we should focus our marketing. Our first stop on the list was House of Tayo, a high-end boutique that focuses on suits, bow ties, ties, and other accessories made of kitenge fabric (the beautiful, wax-printed, brightly patterned fabrics found everywhere here and other countries in East Africa). In talking to Tayo, the shop’s proprietor and a good friend of Kaleigh’s, we learned a lot about how he created a market for his goods. He also works with a women’s cooperative to produce his products, but was not involved so much with the sewing training. He talked a lot about how the climate is probably our biggest barrier as knitted goods are not required for warmth in Rwanda. He suggested that we make bags, tablecloths, or other non-wearable goods as a way around this issue. He also suggested that we use knitted accents on sewn products, just as he has used bright accents of kitenge on solid fabrics. Finally, in regards to the market, he recommended that we don’t limit ourselves to one market, such as schools buying sweaters or expats in need of high-end souvenirs, because all of these markets are seasonal. He thought a combination of different markets would be our best bet. Tayo definitely gave us a lot to think about and to take into consideration when thinking through marketing strategies.

Our second stop was the huge kitenge market in town. There were probably a half dozen rooms inside covered from floor to ceiling in the most amazing fabrics imaginable. We used this time to look at current popular colors and patterns that we might be able to incorporate into knitted goods.

The third stop was at the factory Kaleigh uses to produce the samples of her designs. They used to be associated with a clothing shop based here in Kigali, but when the shop relocated to Kenya, they picked up several contracts with US stores like Anthropologie and Kate Spade and developed a great reputation as an independent manufacturer. We learned from this stop that anything to be exported, a potential eventual goal, must be extremely high in quality.

The final stop on the tour was Sophie’s shop. Sophie, who is currently based in New York, is friend and business partner of Kaleigh’s. She has a small shop with not too much on display because almost all of her business takes the form of custom orders. It turns out most of the clothes here, especially for the more wealthy populations, are made to order. Everyone we have met seems to have their own preferred tailor, and getting clothes made is much cheaper here than in the US. It may be a challenge for the women of the cooperative to meet the need for individualized clothing. This must happen through the use of the creativity, something the women may not know much about yet because their prior products were so systematically produced. Creativity is not something easily taught, but we are up for the challenge!

On Friday we completed our second training in the community—our first with the full time allotment—and then returned to the office to debrief, work on the knitting machine, and prepare next week’s trainings. In the evening we scoped out a coffee shop to get reconnected with family and friends via Skype and then retired to Amber and Yannick’s house for an intern sleepover. Gotta do what ya gotta do for the full internship experience.

On Saturday we spent the day with a UNC alumnus who’s been living in Kigali for the last few years. She teaches at the National University of Rwanda School of Public Health and at Harvard Medical School; she spends most of her time working with Partners in Health here in Rwanda. Pretty rad. She is also a cool contact to have for our public health gurus and Peace Corps hopefuls (she worked for three years in Namibia). It turns out we had actually seen her on Monday at a restaurant trivia night. It’s weird how Kigali is a city of over a million people and yet the community—especially among expats—can seem so small.

Sunday was a restful day spent exercising, sleeping, and eating at Kaleigh and Julie’s house avec Christian: language practice has become an integral part of our day-to-day life. Kinyarwanda, French, and English are intermingled within the house and workplace in collective attempts to communicate.

On Monday we completed our third training in the community. We then returned to the office to work on the knitting machine, debrief the training, and begin to compile a cohesive report on the cooperative’s financial practices/management structure.

Training Report

3 trainings down. 17 to go. That’s pretty scary. We saw a Deloitte office building in Kigali the other day and thought we should maybe stop by for an impromptu help session. “Hi, do you have any advice for a couple of college kids focused on developing a knitting cooperative in a marginalized community with no markets to sell to, limited business experience and limited access to transportation? Oh, and by the way, we can’t speak the same language as the community we are working with.”

It appears that the women in the cooperative are engulfed in their knitting projects, and we’ve been pleased with the overall excitement about knitting. They women are very willing to help each other, which is reflective of the strong community within the cooperative. Oftentimes, one cluster of women surrounding a woman who quickly grasped the concept will progress faster than the others.

Ronah and Nadeg, two of our translators, have been learning the knitting techniques and are incredibly helpful. In the beginning of each training, we demonstrate the skills that we will be teaching in front of the group, with Ronah translating. We then try to keep an eye on each woman to individually help her with the skills, whether that’s correcting or teaching something new. At the third training, we noticed that they have become more comfortable with seeking us out for assistance, which we are happy about. Ronah and Nadeg also work with them individually, calling Sarah and Rachel over when they get stuck. If there is a concept that a woman doesn’t grasp with our lack of verbal communication, we ask Ronah and Nadeg to tell the woman in Kinyarwanda, for example, that she has forgotten to knit the last stitch on a row, that she’s dropped a stitch, or that her stitches are too tight.

Hannah has been keen on both taking attendance and noting the progress of each woman who attends the session. As far as turnout, we have had 20, 17, and 11 members of the cooperative over the three days. We are concerned about the decreasing turnout; Nadeg heard that the husbands of the cooperative members do not want the women to attend the training sessions because they are needed at home. This makes it really tricky for us since we do have so little time to teach skills, and we have to reteach skills to those who didn’t show up. Still, we understand that we are taking a huge chunk of time out of their week and that they have other, more pressing commitments.

The progression of skills that we have taught is casting on, knitting, purling, and ribbing (both knitting and purling within a row). As of the last training, 1 cooperative member is confidently ribbing, 2 are beginning on ribbing, 2 are confident in purling, 3 are confident in knitting, and 3 are still beginning on knitting. We have noticed there is a strong directional divide between those who are progressing quickly and those who are still stuck on the basics of knitting. It also seems like the younger women are picking up skills faster than the older women. Another issue is that they will oftentimes hand us their knitting for help, but we don’t know which stitch they have been trying to do or what they need help with.

For future trainings, we have discussed stratifying into different groups based on skill level. Right now, some women are left behind at the basic skills and lost when we teach new skills, while other women are bored while we review the basics. We are hesitant to form groups, however, because we don’t want any feelings of superiority/inferiority. Tomorrow, we will we start the more advanced women on the hat project.

For our business team, a large part of the first few trainings has been coming to terms with our limitations. As it turns out, we can’t turn a struggling basket weaving cooperative into a Fortune 500 knitting empire in two months. We know, that shouldn’t be shocking. And intellectually it isn’t, but it’s still a blow emotionally. We want to help. We want to make progress. We want to leave in two months with the women confidently knitting Gucci quality sweaters and with contracts secured with local companies to buy their goods. We want that, but we can’t have that. And it does no good to pretend that we can.

Business development takes time. We are here working with HDI because they have been invested in this community for seven years, and will still be here when our two months are up.

We are still trying to figure out what business success on our project looks like. How can we help position HDI to help the community secure markets to sell their knitted goods once the cooperative is ready for that? How can we position the cooperative to be as minimally dependent on the help of HDI as possible?

To this point, our business goals largely take the abstract form of the questions above. We are trying to move towards more concrete objectives, but it takes time.

We’ve used our first few trainings to try and stake down some more concrete things we can focus on. We’ve spent time with our awesome translators Ronah, Claude and Nadeg asking questions of the community. At this point, we probably understand the structure of the cooperative better than anyone at HDI, and probably better than all but a few of the cooperative members!

That last part is rather unfortunate, and is one of the areas we hope to help enact improvements. We are working on writing an outline of the structure and rules of the cooperative for use by HDI. Additionally, we hope to help demystify the way the cooperative operates to its members. The reality is that some of the processes of the cooperative (such as giving out loans with interest) are rather difficult for the women, all of whom never completed secondary school, to understand. As such, there is a gap in understanding between the leaders of the cooperative and many of the members. We hope to help the cooperative bridge this gap by working to find simple and creative ways to explain processes that will resonate with the women.

The abstract nature of our position as business interns leaves lots of room for discussion between Hannah and Connor. It’s cool to see the ways in which their minds work differently and the same. When it comes to helping the cooperative, Connor’s mind tends to jump from one possibility to another, ruling out ones he doesn’t view as feasible, and brainstorming other opportunities. Hannah tends to focus in on what she perceives as critical objectives, and then spend time trying to work around the obstacles to achieve those goals.

It’s easy to caricaturize of Connor’s mind as abstract and theoretical, while Hannah’s leans towards action and productivity. To the extent that these caricatures are true, Connor finds it easier to deal with the limitations of what we are able to achieve in two months. Hannah makes sure we don’t get so caught up looking at the big picture that we forget to accomplish anything. Of course, while it is fun to play around with juxtaposing their personalities in this way, it misses much of the nuance of who they are, and the truly vast expanse of their talents. Connor can still hunker down and get stuff done and Hannah can hold her own in any theoretical conversation.

Together, they are hopeful the next week will further clarify their roles while here, and help them establish more concrete objectives.

Cooperative History

In poring over Google resources for cooperative management, Hannah stumbled upon a Rwanda Cooperative Agency Training Programme; it’s a pretty comprehensive and useful 70-page document that details the history of cooperatives in East Africa, and specifically Rwanda. Reading through it has brought to light a lot of things we had questioned regarding the egalitarian structure of cooperatives and their relationship to local governments. The larger use of this document is to provide a more common ground on which we can have conversations with the cooperative, because drawing answers to structural and value-based questions can be difficult with translators and limited time.

Cooperatives were originally instated by colonial governments, but were later encouraged post-independence as they fit with African socialist and humanist movements. After the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, Rwanda’s population was 70% female, thus cooperatives were further encouraged by the government as a way to harness the economic potential of women in producing consumer goods and restoring community bonds. They serve as both economic and political units, both public organizations and private-sector businesses.

Principles of a cooperative:

Voluntary and open membership

Democratic member control

Member economic participation

Autonomy and participation

Education, training, and information

Cooperation among cooperatives (lol)

Concern for community

Values of a cooperative:

Self-responsibility

Democracy

Equality

Equity

Solidarity

Honesty

Openness

Social responsibility

Caring for others

Getting a better understanding of these values will educate the way we interact with the cooperative and the ways in which we try to empathize with their style of management to help them accomplish their goals. These values are becoming more and more apparent in our conversations with the cooperative leaders; for example, in our last training the leaders spoke to us about the possibility of assigning a point person to be in charge of selling all the cooperative goods to potential buyers in an effort to reduce competition amongst the women. We struggle a little bit to reconcile the largely egalitarian cooperative attitude with the efficiency offered by a more specialized leadership structure; though, to be fair, specialization is not so much an enemy to egalitarianism as hierarchy is. We will continue to work with the cooperative in a sensitive manner, especially when delving into finance and management practices that have the potential to affect their current model.

Cultural Differences

We continue to be observant of cultural differences. The punctuality difference remains, which we were reminded of while waiting for an hour and a half at a restaurant, despite being literally the only costumers present. There is also a difference in personal space, especially on public transit and on sidewalks. No one really minds bumping into each other, even if it seems easily avoidable. Men are noticeably more touchy with each other – we oftentimes see two men holding hands or sitting on each others’ laps, which is uncommon back home (side note about the male sex: it doesn’t seem culturally unacceptable to leave the toilet seat up).

We have also been amusedly noticing English phrases, especially on clothing, that the wearers probably (hopefully?) don’t understand such as, “All you need is LOL” and an older man rocking a ∆∆∆ sweatshirt. There is also a cafe that promises “tea with very taste,” whatever that means. Schoolkids especially love to yell “Good morning!” after noticing our white skin, even if it’s at 6pm. They also exclusively reply to “How are you?” with “I’m fine, thanks.”

Socially, an invitation to something like lunch automatically means that the inviter is paying. For this reason, people oftentimes run out of money by the end of the working month. Lastly, conversations about family are very different in Rwanda. Rwandese ask us “Do you have two parents?” rather than, “What do your parents do?” The assumption is not that both parents are alive, as it is in the United States. This semantic difference is a good representation of historical and health differences between Rwanda and the US.

Next Steps

In the coming days, we will continue to conduct trainings in the community on Wednesday and Friday, planning our time and assessing our progress. We’re hoping to extend our time in the community in any way we can while remaining respectful of the time community members can dedicate to spending with us. We are in the process of planning a trip to Lake Kivu this weekend, which should be awesome. We have been invited to a wedding in Claude’s family next weekend and are excited in preparation for that. In the meantime, we’ll keep you updated.

Looking forward,

HDI Team

P.S. Sarah has also learned how to knit hair. Possibilities for the future are ever-widening.